By Ximena Gonzalez, Alliance for Sustainability Intern, The University of Texas at Austin ‘23

The dream of urban life is that cities will provide equal opportunities to everyone for education, social mobility, amenities, culture, connection and expression. Unfortunately, this is not and has not been the reality, both in the US and around the world. In fact, the affluent live very different lives from those who live in poverty in the same city. As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said more than 50 years ago in 1968:

Every city in our country has this kind of dualism…

every city ends up being two cities rather than one. There are two Americas.

Cities have always been a display for inequality in this country, and the Covid-19 pandemic has only emphasized this inequity now more than ever.

Historical Inequity in Cities

Inequality in American cities is a systemic issue, literally built into the ways our neighborhoods are zoned, where parks are planned, and how our streets look. For example, public institutions like schools and libraries are often funded by the property taxes of people in those districts. This means that private wealth buys the quality of public resources. Affluent areas with high property taxes have schools and libraries that are well-funded, giving kids every opportunity to succeed. Or as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “In this America children grow up in the sunlight of opportunity.”

Neighborhoods with lower socioeconomic statuses and lower property tax revenue have schools that are not well-funded. This means teachers don’t get paid enough, students are not given the resources they need, and there are higher dropout rates. As King said,“In this other America… the schools are so inadequate, so over-crowded, so devoid of quality, so segregated if you will, that the best in these minds can never come out.”

Beyond that, inequality in cities can be seen in multiple other aspects of city life:

- People with lower incomes, who are often part of marginalized communities, are less likely to own a car but are more likely to feel the effects of air pollution. This is often due to pollution sources being located closer to these communities and their having less healthcare resources available when health complications due to pollution do come up.

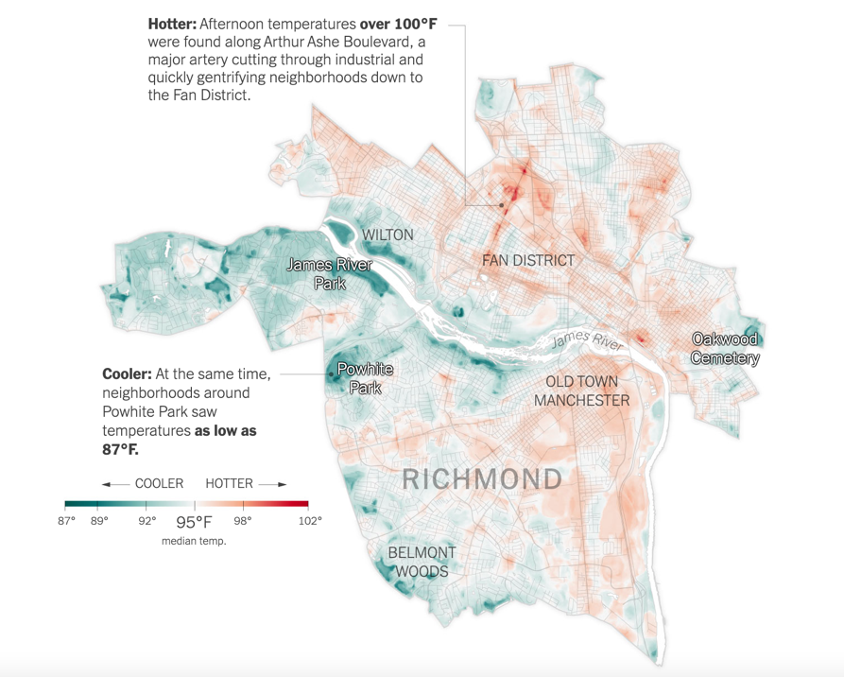

- Poor or minority neighborhoods are more likely to be in urban heat islands, or areas of the city that are significantly hotter than other areas. It can be up to a 20℉ difference. These neighborhoods have less green space which helps cool down surrounding areas.

- There is rarely affordable housing in more affluent commercial areas, meaning low-income workers might not be able to afford to live close to their place of work. This means longer commute times, often on unavailable or unreliable public transportation.

Source: New York Times

Covid’s Impact on Inequity in Cities

The Covid pandemic has only emphasized the inequities of city life. Covid has unequally affected racial and ethnic minority groups since they are more likely to get the virus. This is often due to their living conditions, their modes of transportation, and their access to healthcare:

- Lower income people are more likely to live in crowded housing. This makes it easier to get the virus, and it also makes it harder to quarantine from others.

- These minority groups are also more likely to be essential workers. They do not have the choice to work from home, so they must expose themselves to potential risk every day. Additionally, they are more likely to take public transportation to work meaning that is one more crowded place where they might get the virus.

- Lower income people also do not have the option to simply get up and leave a densely populated city and head to the suburbs. They cannot afford to leave their jobs, their communities, or their homes. They cannot escape disease so easily.

In conclusion, the benefits and burdens of urban living aren’t equally shared. Poor people are negatively impacted by the disparities on many levels. It should be a top priority to address this inequity.

As we will explore in Part 2, the good news is that there are progressive, green, and just solutions to many of these urban inequities that will help lift people out of poverty, increase accessibility and make communities more resilient. And more often than not, when the most marginalized communities benefit, almost all city dwellers benefit. However, it is important to remember that inequity of any sort is always complex, systemic, and often historical. This means solutions must be multi-pronged, flexible, and cautious about creating further challenges. Solutions to help cities are solutions to help people.